Metallurgical Traditions in West Africa: Technology, Production, and Exchange of Iron and Copper in Nigeria from 700 BC to AD 1800 (METALS)1

The METALS project focuses on Nigeria’s early metallurgy in its wider West African context, combining continent-wide networks such as the trans-Saharan trade routes from Morocco and Mali through Ghana and Nigeria into the rain forest of Cameroon and Central Africa, with the extra-African maritime connections to Arab and European agents, discussing the import of metal from further afield. For this, the project combines the study of West African metal objects in various museums and excavation archives in the US, Europe and West Africa, with fieldwork in Nigeria and Ghana to include recent and current excavation material into the pool of archaeological remains to be analysed. After the fieldwork, the Fellow, Dr Abidemi Babalola, works with the Host supervisor in the STARC laboratory, using hhXRF analysis, sample preparation, and optical and scanning electron microscopy to analyse slags, crucibles, and metal artefacts.

Copper-lead objects from Gao, Mali

Gao was one of the West African Medieval cities with some coverage in the Arab chronicles, providing unambiguous accounts of its existence and, to a large extent, function. For example, the vibrancy of Gao in trade was documented by early Arab writers (referred to as Gawgaw), who stated that it derived its wealth and power from controlling the desert salt trade. Also, a 10th-century CE Arab chronicler mentioned two towns of Gao (Gawgaw): one the market and trading town (Sarneh), and the other the royal town (Ancien) with the king’s palace. Probably established in the 8th century, by the 9th and through to the 11th centuries Gao was a well-established commercial city connected with the North Africa state of Tahert, and other major trading towns such as Tiraqqa and Tadmekka. Gao remained a major Islamic city and famous among the Arab traders until it was conquered in the late 16th century CE and the commercial focus shifted to Timbuktu further west.

Copper-related metal artefacts or ingots are major trade items across the Sahara. The famous 1000 kg hoard of brass ingots in the ‘lost caravan’ shows the intercontinental scale of this metal trade, with tentative connections as far north as England. As such, several studies have focused on identifying the sources of the metals for copper objects,and Tunisian, Algerian, and Moroccan mines have been proposed as candidates. Several 1st millennium CE West African copper metals and alloys from Kissi, Essouk, Marandet, Azelik and Igbo-Ukwu point to potential ore exploitation in Tunisia. It has been suggested that copper from Iraqi and Iranian sources could have also reached West Africa in the late 1st millennium CE. Several samples of leaded copper and brass have also emerged from Essouk-Tadmekka. Ongoing research at STARC identified contemporary copper and lead smelting in southern Morocco at Tamdult.

Due to the massive looting by the locals for glass beads, Malian archaeologist Mamadou Cisse and his team embarked on an archaeological investigation at Gao Saney in 2001 and 2002, which continued in 2009. Cisse excavated two units in 2001-2 named GS1 and GS3, measuring 3 x 3 meters and 3 x 2 meters. In 2009, unit ACGS measuring 3 x 3 meters was excavated two meters from GS1. The units yielded abundant copper-related materials, including 170 clay crucibles, about 1.8 kg of melted copper, and over 800 copper-based finds, over 400 of which are fragments of copper crescents.

Cross-section through the best-preserved sample (GKM 13), showing a distinct dendritic texture of the copper (light orange colour) with some porosity (black) and widespread corrosion (various grey shades). Panoramic micrograph at 2.5x

Lead Isotope Analyses are ongoing in collaboration with the KU Leuven to explore any potential link of the metal artefacts to a specific geological source region.

Copper alloys from Ghana

In Ghana, Dr Babalola visited the Ghana National Museum and was provided access to two assemblages. One large collection, based on excavations in Banda by Professor Ann Stahl from between 2000 and 2009, consists primarily of metal fragments such as wire, sheet, etc. as well as complete diagnostic objects, e.g. bangles, rings, earrings, and figurines. They cut across the 13th through 19th century.

The other Ghanan assemblage is from the site of Begho which was first excavated in 1970 and again in 1975 by Merrick Posnasky. Reports on the 1970s excavation indicated that about 500 possible copper-alloy casting crucibles were linked to copper metallurgy based on archaeological assessment and visual inspection. Similar material had been studied in the 1970s, with preliminary results indicating a high copper content in some of the vessels.

Brass crucibles from Ghana, showing a range of sizes.

Cross section through brass crucible from Ghana, showing a clear layering of ceramic. The crucible fabric contains several percent by weight zinc, demonstrating the vessel’s use for brass metallurgy.

Nigerian iron metallurgy

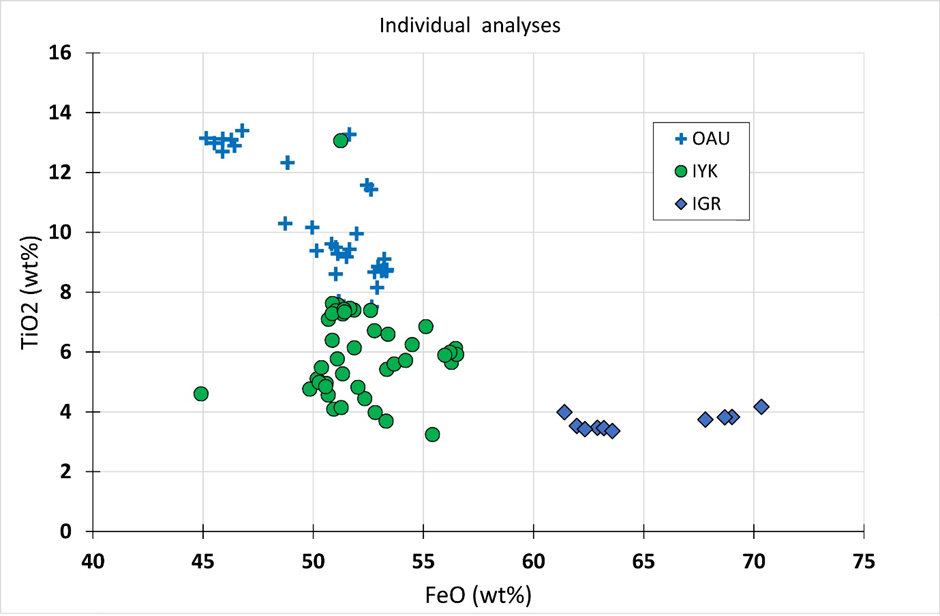

In Nigeria, Dr Babalola is overseeing excavations of early historical to recent iron smelting. Initial results demonstrate that the ore was extremely rich in titania, indicating the use of ilmenite-rich ‘black sand’ as an ore.

1This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 101038069.